Networking Models

Computer networks consist of many different components and protocols working together. To understand the concept of how node to node communication happens, let's get familiar to the OSI model and TCP/IP model. Both models help to visualize how communication between nodes is happening.

OSI Model

The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) model is a 7-layer model that today is used as a teaching tool. The OSI model was originally conceived as a standard architecture for building network systems, but in real-world networks are much less defined than the OSI model suggests.

- Layer 7 (Application) - a protocol that defines the communication between the server and the client, for example, HTTP protocol. If the web browser wants to download an image, the protocol will organize and execute the request;

- Layer 6 (Presentation) - ensures data is received in a usable format. Encryption is done here (but in reality it may not be true, for example, IPSec);

- Layer 5 (Session) - responsible for setting up, managing and closing sessions between client and server;

- Layer 4 (Transport) - transport layers primary responsibility is assembly and reassembly, a data stream is divided into chunks (segments), assigned sequence numbers and encapsulated into protocol header (TCP, UDP, etc.);

- Layer 3 (Network) - responsible for logical device addressing, data is encapsulated within an IP header and now called "packet";

- Layer 2 (Data link) - Data is encapsulated within a custom header, either 802.3 (Ethernet) or 802.11 (wireless) and is called "frame", handles flow control;

- Layer 1 (Physical) - Communication media that sends and receives bits, electric signaling, and hardware interface;

TCP/IP Model

This model has the same purpose as the OSI model but fits better into modern network troubleshooting. Comparing to the OSI model, TCP/IP is a 4-layer model:

- Application layer (4) - includes application, presentation and session layers of the OSI model, which significantly simplifies network troubleshooting;

- Transport layer (3) - same as a transport layer in the OSI model (TCP, UDP protocols);

- Internet layer (2) - does the same as Network layer in the OSI model (include ARP, IP protocols);

- Link layer (1) - also called the Network Access layer. Includes both Layer1 and 2 of the OSI model, therefore its primary concern is physical data exchange between network nodes;

|

Ethernet

The most commonly used link layer protocol (OSI Layer2) in computer networks is the Ethernet protocol. In order to communicate, each node has a unique assigned address, called MAC (Media Access Control address) sometimes it is also called an Ethernet address.

It is 48-bit long and typically fixed by the manufacturer (cannot be changed), but in recent years customization of MAC addresses is widely used, RouterOS also allows to set custom MAC address.

Most commonly used MAC format is 6 hexadecimal numbers separated by colons (D4:CA:6D:01:22:96)

RouterOS shows MAC address in a configuration for all Ethernet-like interfaces (Wireless, 60G, VPLS, etc.)

[admin@rack1_b32_CCR1036] /interface ethernet> print Flags: X - disabled, R - running, S - slave # NAME MTU MAC-ADDRESS ARP SWITCH 0 R ether1 1500 D4:CA:6D:01:22:96 enabled 1 R ether2 1500 D4:CA:6D:01:22:97 enabled 2 R ether3 1500 D4:CA:6D:01:22:98 enabled 3 ether4 1500 D4:CA:6D:01:22:99 enabled 4 ether5 1500 D4:CA:6D:01:22:9A enabled 5 ether6 1500 D4:CA:6D:01:22:9B enabled 6 ether7 1500 D4:CA:6D:01:22:9C enabled 7 R ether8 1500 D4:CA:6D:01:22:9D enabled 8 sfp-sfpplus1 1500 D4:CA:6D:01:22:94 enabled 9 sfp-sfpplus2 1500 D4:CA:6D:01:22:95 enabled |

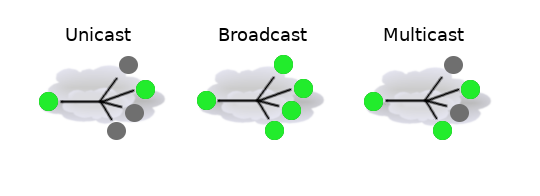

There are three types of addresses:

Unicast address is sent to all nodes within the collision domain, which typically is Ethernet cable between two nodes or in case of wireless all receivers that can detect wireless signals. Only remote node with matching MAC address will accept the frame (unless the promiscuous mode is enabled)

One of the special addresses is broadcast address (

FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF), a broadcast frame is accepted and forwarded over Layer2 network by all nodesAnother special address is multicast. Frames with multicast addresses are received by all nodes configured to receive frames with this address.

IP Networking

Ethernet protocol is sufficient to get data between two nodes on an Ethernet network, but it is not used on its own. For Internet/Networking layer (OSI Layer 3) IP (Internet Protocol) is used to identify hosts with unique logical addresses.

Most of the current networks use IPv4 addresses, which are 32bit address written in dotted-decimal notation (192.168.88.1)

There can be multiple logical networks and to identify which network IP address belongs to, the netmask is used. Netmask typically is specified as a number of bits used to identify a logical network. The format can also be in decimal notation, for example, the 24-bit netmask can be written as 255.255.255.0

Let's take a closer look at 192.168.3.24/24:

11000000 10101000 00000011 00011000 => 192.168.3.24 11111111 11111111 11111111 00000000 => /24 or 255.255.255.0 |

As can be seen from the illustration above high 24 bits are masked, leaving us with a range of 0-255.

From this range, the first address is used to identify the network (in our example network address would be 192.168.3.0) and the last one is used for network broadcast (192.168.3.255). That leaves us with a range from 1 to 254 for host identification which is called unicast addresses.

The same as in Ethernet protocol there can be also special addresses:

- broadcast - address to send data to all possible destinations ("all-hosts broadcast"), which permits the sender to send the data only once, and all receivers receive a copy of it. In the IPv4 protocol, the address 255.255.255.255 is used for local broadcast. In addition, a directed (limited) broadcast can be made to network broadcast address;

- multicast - address associated with a group of interested receivers. In IPv4, addresses

224.0.0.0through239.255.255.255are designated as multicast addresses. The sender sends a single datagram from its unicast address to the multicast group address and the intermediary routers take care of making copies and sending them to all receivers that have joined the corresponding multicast group;

In case of logical IP network, unicast, broadcast and multicast visualization would look a bit different

There are also address ranges reserved for a special purpose, for example, private address range, that should be used only in local networks and typically are dropped when forwarded to the internet:

- 10.0.0.0/8 - start: 10.0.0.0; end: 10.255.255.255

- 172.16.0.0/12 - start: 172.16.0.0; end:172.31.255.255

- 192.168.0.0/16 - start: 192.168.0.0; end: 192.168.255.255

ARP and Tying It All Together

Even though IP packets are addressed using IP addresses, hardware addresses must be used to actually transport data from one host to another.

This brings us to Address Resolution Protocol (ARP) which is used for mapping the IP address of the host to the hardware address (MAC). ARP protocol is referenced in RFC 826.

Each network device has a table of currently used ARP entries. Normally the table is built dynamically, but to increase network security, it can be partially or completely built statically by means of adding static entries.

Address Resolution Protocol is a thing of the past. IPv6 completely eliminates use of the ARP. |

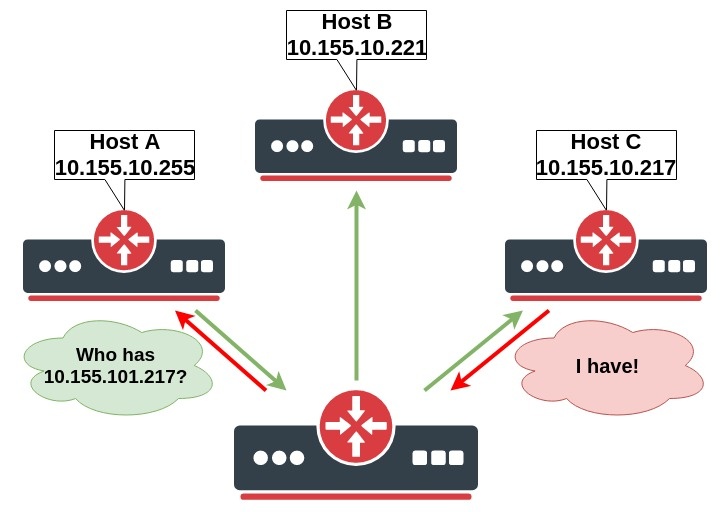

When a host on the local area network wants to send an IP packet to another host in this network, it must look for the Ethernet MAC address of destination host in its ARP cache. If the destination host’s MAC address is not in the ARP table, then the ARP request is sent to find the device with a corresponding IP address. ARP sends a broadcast request message to all devices on the LAN by asking the devices with the specified IP address to reply with its MAC address. A device that recognizes the IP address as its own returns ARP response with its own MAC address:

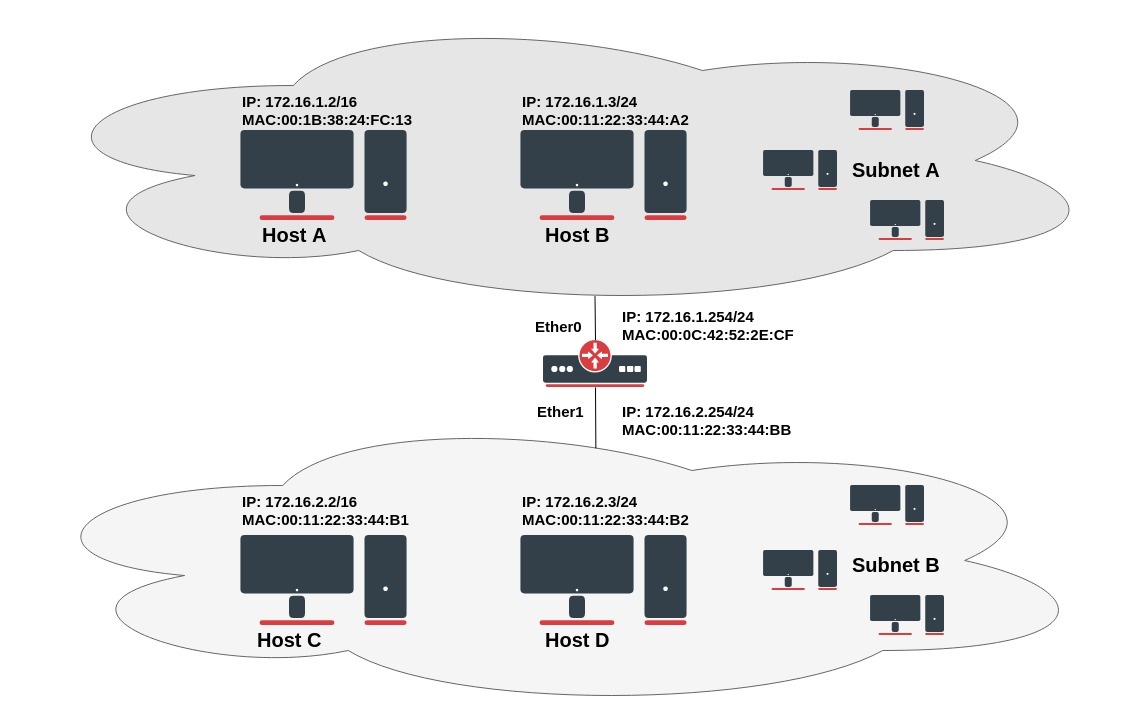

Let's make a simple configuration and take a closer look at processes when Host A tries to ping Host C.

At first, we add IP addresses on Host A:

/ip address add address=10.155.101.225 interface=ether1 |

Host B:

/ip address add address=10.155.101.221 interface=ether1 |

Host C:

/ip address add address=10.155.101.217 interface=ether1 |

Now, let's run a packet sniffer that saves packet dump to the file and run the ping command on Host A:

/tool sniffer set file-name=arp.pcap filter-interface=ether1 start /ping 10.155.101.217 count=1 stop |

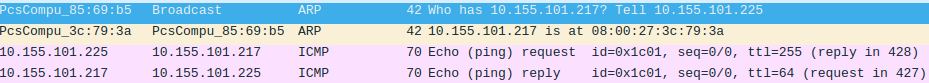

Now you can download arp.pcap file from the router and open it in Wireshark for analyzing:

- Host A sends ARP message asking who has "10.155.101.217"

- Host C responds that 10.155.101.217 can be reached at 08:00:27:3C:79:3A MAC address

- Both Host A and Host C now have updated their ARP tables and now ICMP (ping) packets can be sent

If we look at ARP tables of both host we can see relevant entries, in RouterOS ARP table can be viewed by running command: /ip arp print

[admin@host_a] /ip arp> print Flags: X - disabled, I - invalid, H - DHCP, D - dynamic, P - published, C - complete # ADDRESS MAC-ADDRESS INTERFACE 0 DC 10.155.101.217 08:00:27:3C:79:3A ether1 [admin@host_b] /ip arp> print Flags: X - disabled, I - invalid, H - DHCP, D - dynamic, P - published, C - complete # ADDRESS MAC-ADDRESS INTERFACE 0 DC 10.155.101.225 08:00:27:85:69:B5 ether1 |

ARP Modes

Now the example above demonstrated default behavior, where ARP is enabled on interfaces, but there might be scenarios where different ARP behavior is necessary. RouterOS allows configuring different ARP modes for interfaces that support ARP.

Enabled

ARPs will be discovered automatically and new dynamic entries will be added to the ARP table. This is a default mode for interfaces in RouterOS and illustrated in the example above.

Disabled

If the ARP feature is turned off on the interface, i.e., arp=disabled is used, ARP requests from clients are not answered by the router. Therefore, static ARP entry should be added to the clients as well. For example, the router's IP and MAC addresses should be added:

[admin@host_a] > /ip arp add mac-address=08:00:27:3C:79:3A address=10.155.101.217 interface=ether1 |

Reply Only

If the ARP property is set to reply-only on the interface, then the router only replies to ARP requests. Neighbour MAC addresses will be resolved using /ip arp statically, but there will be no need to add the router's MAC address to other hosts' ARP tables like in cases where ARP is disabled.

Proxy ARP

A router with properly configured proxy ARP feature acts as a transparent ARP proxy between directly connected networks. This behavior can be useful, for example, if you want to assign dial-in (PPP, PPPoE, PPTP) clients IP addresses from the same address space as used on the connected LAN.

Let's look at the example setup from the image above. Host A (172.16.1.2) on Subnet A wants to send packets to Host D (172.16.2.3) on Subnet B. Host A has a /16 subnet mask which means that Host A believes that it is directly connected to all 172.16.0.0/16 network (the same LAN). Since the Host A believes that is directly connected it sends an ARP request to the destination to clarify the MAC address of Host D. (in the case when Host A finds that destination IP address is not from the same subnet it sends a packet to the default gateway.). Host A broadcasts an ARP request on Subnet A.

Info from packet analyzer software:

No. Time Source Destination Protocol Info

12 5.133205 00:1b:38:24:fc:13 ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff ARP Who has 173.16.2.3? Tell 173.16.1.2

Packet details:

Ethernet II, Src: (00:1b:38:24:fc:13), Dst: (ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff)

Destination: Broadcast (ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff)

Source: (00:1b:38:24:fc:13)

Type: ARP (0x0806)

Address Resolution Protocol (request)

Hardware type: Ethernet (0x0001)

Protocol type: IP (0x0800)

Hardware size: 6

Protocol size: 4

Opcode: request (0x0001)

[Is gratuitous: False]

Sender MAC address: 00:1b:38:24:fc:13

Sender IP address: 173.16.1.2

Target MAC address: 00:00:00:00:00:00

Target IP address: 173.16.2.3 |

With this ARP request, Host A (172.16.1.2) is asking Host D (172.16.2.3) to send its MAC address. The ARP request packet is then encapsulated in an Ethernet frame with the MAC address of Host A as the source address and a broadcast (FF:FF:FF:FF:FF:FF) as the destination address. Layer 2 broadcast means that frame will be sent to all hosts in the same layer 2 broadcast domain which includes the ether0 interface of the router, but does not reach Host D, because router by default does not forward layer 2 broadcasts.

Since the router knows that the target address (172.16.2.3) is on another subnet but it can reach Host D, it replies with its own MAC address to Host A.

No. Time Source Destination Protocol Info 13 5.133378 00:0c:42:52:2e:cf 00:1b:38:24:fc:13 ARP 172.16.2.3 is at 00:0c:42:52:2e:cf Packet details: Ethernet II, Src: 00:0c:42:52:2e:cf, Dst: 00:1b:38:24:fc:13 Destination: 00:1b:38:24:fc:13 Source: 00:0c:42:52:2e:cf Type: ARP (0x0806) Address Resolution Protocol (reply) Hardware type: Ethernet (0x0001) Protocol type: IP (0x0800) Hardware size: 6 Protocol size: 4 Opcode: reply (0x0002) [Is gratuitous: False] Sender MAC address: 00:0c:42:52:2e:cf Sender IP address: 172.16.1.254 Target MAC address: 00:1b:38:24:fc:13 Target IP address: 172.16.1.2 |

This is the Proxy ARP reply that the router sends to Host A. Router sends back unicast proxy ARP reply with its own MAC address as the source address and the MAC address of Host A as the destination address, by saying "send these packets to me, and I'll get it to where it needs to go."

When Host A receives ARP response it updates its ARP table, as shown:

C:\Users\And>arp -a Interface: 173.16.2.1 --- 0x8 Internet Address Physical Address Type 173.16.1.254 00-0c-42-52-2e-cf dynamic 173.16.2.3 00-0c-42-52-2e-cf dynamic 173.16.2.2 00-0c-42-52-2e-cf dynamic |

After MAC table update, Host A forwards all the packets intended for Host D (172.16.2.3) directly to router interface ether0 (00:0c:42:52:2e:cf) and the router forwards packets to Host D. The ARP cache on the hosts in Subnet A is populated with the MAC address of the router for all the hosts on Subnet B. Hence, all packets destined to Subnet B are sent to the router. The router forwards those packets to the hosts in Subnet B.

Multiple IP addresses by the host are mapped to a single MAC address (the MAC address of this router) when proxy ARP is used.

Proxy ARP can be enabled on each interface individually with command arp=proxy-arp:

[admin@MikroTik] /interface ethernet> set 1 arp=proxy-arp [admin@MikroTik] /interface ethernet> print Flags: X - disabled, R - running # NAME MTU MAC-ADDRESS ARP 0 R ether1 1500 00:30:4F:0B:7B:C1 enabled 1 R ether2 1500 00:30:4F:06:62:12 proxy-arp [admin@MikroTik] interface ethernet> |

Local Proxy ARP

if the arp property is set to local-proxy-arp on an interface, then the router performs proxy ARP to/from this interface only. I.e. for traffic that comes in and goes out of the same interface. In a normal LAN, the default behavior is for two network hosts to communicate directly with each other, without involving the router.

This is done to support (Ethernet) switch features, like RFC 3069, where the individual ports are NOT allowed to communicate with each other, but they are allowed to talk to the upstream router. As described in RFC 3069, it is possible to allow these hosts to communicate through the upstream router by proxy_arp'ing. Don't need to be used together with proxy_arp. This technology is known by different names:

- In RFC 3069 it is called VLAN Aggregation;

- Cisco and Allied Telesis call it Private VLAN;

- Hewlett-Packard calls it Source-Port filtering or port-isolation;

- Ericsson calls it MAC-Forced Forwarding (RFC Draft).

TCP/IP

TCP Session Establishment and Termination

TCP is a connection-oriented protocol. The difference between a connection-oriented protocol and a connection-less protocol is that a connection-oriented protocol does not send any data until a proper connection is established.

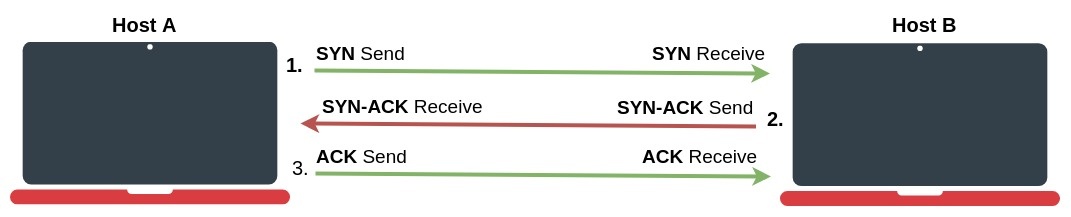

TCP uses a three-way handshake whenever the transmitting device tries to establish a connection to the remote node. As a result end-to-end virtual (logical) circuit is created where flow control and acknowledgment for reliable delivery are used. TCP has several message types used in connection establishment and termination process.

Connection establishment process

- The host A who needs to initialize a connection sends out an SYN (Synchronize) packet with a proposed initial sequence number to the destination "host B";

- When the host B receives an SYN message, it returns a packet with both SYN and ACK flags set in the TCP header (SYN-ACK);

- When the host A receives the SYN-ACK, it sends back the ACK (Acknowledgment) packet;

- Host B receives ACK and at this stage, the connection is ESTABLISHED;

Connection-oriented protocol services are often sending acknowledgments (ACKs) after successful delivery. After the packet with data is transmitted, the sender waits for acknowledgment from the receiver. If time expires and the sender did not receive ACK, a packet is retransmitted.

Connection termination

When the data transmission is complete and the host wants to terminate the connection, the termination process is initiated. Unlike TCP Connection establishment, which uses a three-way handshake, connection termination uses four-way massages. A connection is terminated when both sides have finished the shutdown procedure by sending a FIN (finish) and receiving an ACK (Acknowledgment).

- The host A, who needs to terminate the connection, sends a special message with the FIN flag, indicating that it has finished sending the data;

- The host B, who receives the FIN segment, does not terminate the connection but enters into a "passive close" (CLOSE_WAIT) state and sends the ACK for the FIN back to the host A. If host B does not have any data to transmit to the host A it will also send the FIN message. Now the host B enters into LAST_ACK state. At this point host B will no longer accept data from host A, but can continue to transmit data to host A.

- When the host A receives the last FIN from the host B, it enters into a (TIME_WAIT) state, and sends an ACK back to the host B;

- Host B gets the ACK from the host A and connection is terminated;

TCP Segments transmission (windowing)

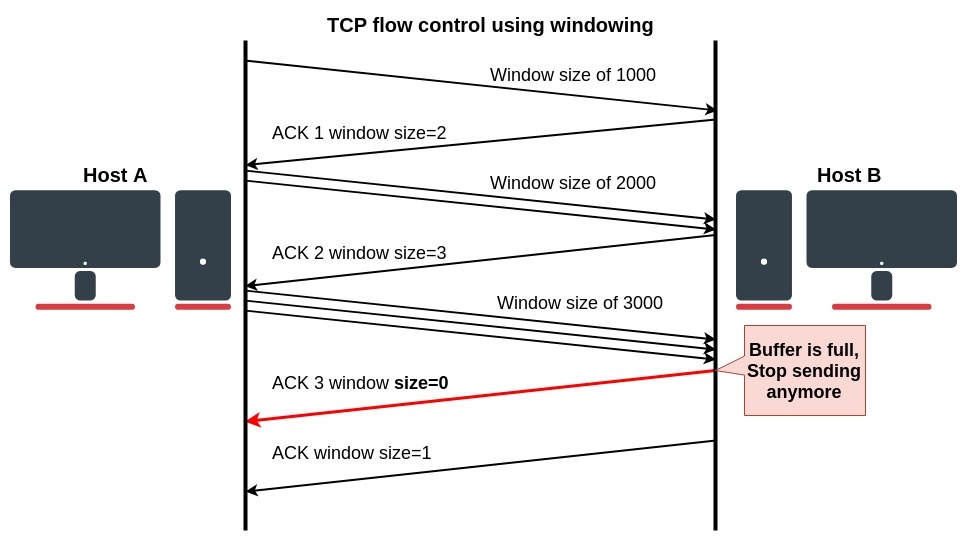

Now that we know how the TCP connection is established we need to understand how data transmission is managed and maintained. In TCP/IP networks transmission between hosts is handled by TCP protocol.

Let’s think about what happens when data-grams are sent out faster than the receiving device can process. The receiver stores them in memory called a buffer. But since buffer space is not unlimited, when its capacity is exceeded receiver starts to drop the frames. All dropped frames must be re-transmitted again which is the reason for low transmission performance.

To address this problem, TCP uses a flow control protocol. The window mechanism is used to control the flow of the data. When a connection is established, the receiver specifies the window field in each TCP frame. Window size represents the amount of received data that the receiver is willing to store in the buffer. Window size (in bytes) is sent together with acknowledgments to the sender. So the size of the window controls how much information can be transmitted from one host to another without receiving an acknowledgment. The sender will send only the amount of bytes specified in window size and then will wait for acknowledgments with updated window size.

If the receiving application can process data as quickly as it arrives from the sender, then the receiver will send a positive window advertisement (increase the size of the window) with each acknowledgment. It works until the sender becomes faster than the receiver and incoming data will eventually fill the receiver's buffer, causing the receiver to advertise acknowledgment with a zero window. A sender that receives a zero window advertisement must stop transmit until it receives a positive window. Let's take a look at the illustrated windowing process:

- The "host A" starts to transmit with a window size of 1000, one 1000byte frame is transmitted;

- Receiver "host B" returns ACK with window size to increase to 2000;

- The host A receives ACK and transmits two frames (1000 bytes each);

- After that, the receiver advertises an initial window size to 3000. Now sender transmits three frames and waits for an acknowledgement;

- The first three segments fill the receiver's buffer faster than the receiving application can process the data, so the advertised window size reaches zero indicating that it is necessary to wait before further transmission is possible;

- The size of the window and how fast to increase or decrease the window size is available in various TCP congestion avoidance algorithms such as Reno, Vegas, Tahoe, etc;